WALLACE CHAN: TOTEM

Curated by James Putnam

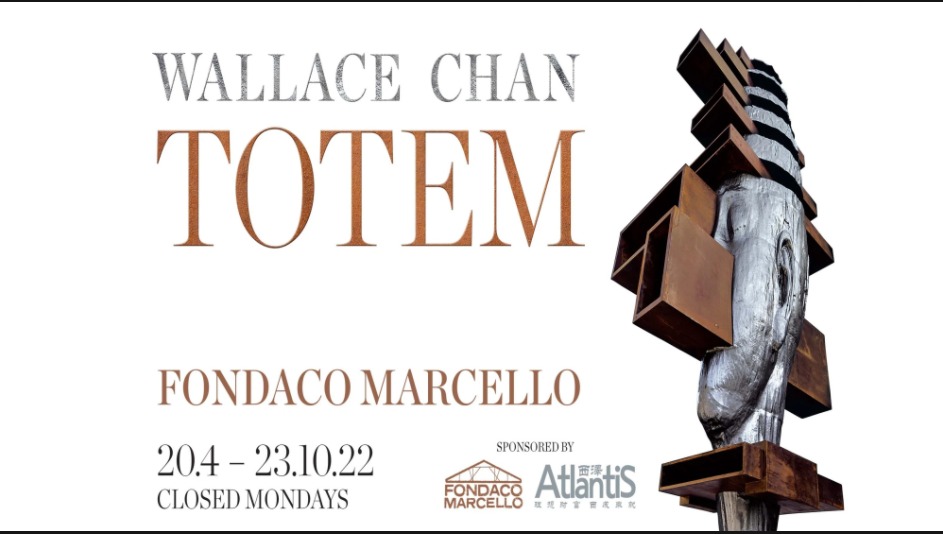

Chinese multidisciplinary artist Wallace Chan, who has pioneered titanium’s unprecedented use for large-scale sculptures, will present his sculpture exhibition TOTEM at the Fondaco Marcello in Venice, launching during the opening week of the 59th Venice Biennale.

In the first place, the totem is the common ancestor of the clan; at the same time it is their guardian spirit and helper, which sends them oracles. — Sigmund Freud

Totem is a large-scale installation of the unassembled parts of Wallace Chan’s 10-metre-high sculpture made of iron beams and carefully modelled titanium heads of various sizes. The installation presents an interactive relationship between the work and the exhibition space, encouraging viewers to approach the parts closely and to view them from various angles. Chan invites visitors to experience these different perspectives as they wander among the sculptural elements, transforming their static completeness into an expansive ‘universe’ composed of many parts.

The term totem usually refers to a revered ancestral spirit and is connected to a primal belief that the universe and everything in nature has a soul and that totems are symbols of human connections with all living and inanimate things. The reoccurring enigmatic face in Chan’s sculptures is a spiritual being, a kind of personification of our planet and its natural energy. It is the interconnection of the Earth’s separate parts that enables it to regulate its own environment and to be habitable and capable of sustaining human life. By presenting his ‘Totem’ sculpture in unassembled parts, Chan alludes to the need for its reconstruction by displaying an assembly diagram on the gallery walls.

The enigmatic face motif is one of the defining characteristics of Chan’s imagination. Its ageless and androgynous facial features have a serene aura, as if to reference Buddhist imagery. While it resembles an ancient archetype, it possesses a timeless quality belonging to both past and future, with a somewhat uncanny aura, like an extra-terrestrial. The recurrent versions of the face at different scales are made from titanium, the strongest, most durable and lightweight metal known. Chan has pioneered its unprecedented use for large-scale sculptures.

By juxtaposing the titanium faces with the iron beams, Chan sets up a dialogue between the two materials, with the lightness and durability of titanium providing a dramatic contrast to the weightiness and susceptibility to corrosion of iron. Chan is sensitive to the character of the metals he works with and believes that the inanimate materials possess some innate metaphysical energy or life force. His skill at creating both miniature and monumental sculptures seems to give him unique insight into the connection between the Microcosm and Macrocosm that characterises his practice. With his background in Buddhist philosophy, the work is linked to contemplation and curiosity about life, nature and the mysteries of the universe.

The spectacle of Chan’s installation does not belong to a singular form; rather, it is produced by the relationship between its multiple parts. Once disassembled, the integrity of the sculpture as a unified form is removed, suggesting the fragility and imminent collapse of a previous order. It symbolises both social and psychological fragmentation in the current atmosphere of uncertainty over global issues, such as polarised politics, climate change and pollution. Chan’s fragmentary sculpture can also be perceived as the vestiges of some lost civilization or a memorial to a distant primordial existence.

This can be appreciated as a series of conceptual and formal distinctions between the sculpture and the ground beneath us, as different arrangements of both figurative and abstract physical mass. Their experience is intended to feel their way into the sculptural space from within and become almost part of the sculpture at both its centre and periphery.

Titanium is the strongest, most durable and lightweight metal known. After eight years of research and experimentation, Wallace Chan started using titanium, first for jewellery and then for large-scale sculptures. After considerable experimentation, he discovered how to work with titanium and has recently created large sculptures with it.

The central motif of the sculptures is the colossal head, whose facial features are calm, with a peaceful aura and enigmatic expression that seems to reference Buddhist imagery. It evokes both past and future, as it can represent either an ancient archetype or an extra-terrestrial. The sculptures are quite complex and feature smaller versions of the head occasionally ‘framed’ within a square configuration of iron girders.

Chan uses this device, with the recursive smaller version of his sculpture becoming an even smaller version, to evoke the notion of infinity and its relationship with space and time. Chan has a similar penchant for using distortion, deconstruction and fragmentation, which has precedent in art history in both Baroque and Postmodern sculpture. The sculptures convey a sense of concentration, inviting the viewer’s gaze to penetrate their peaceful, idealised Buddha-like faces with exaggerated ears, features that have their origins in the gemstone carvings of goddesses he made in his formative years.

The sculpture’s recurrent motif is an enigmatic face, which is the dominant motif in his sculptures and one of the defining characteristics of Chan’s imagination. This is reproduced in different scales and sizes. The central largest fragmentary head forms part of a 5m sculpture that was exhibited earlier this year at Canary Wharf, London.

The unassembled sculpture suggests the fragility and imminent collapse of a previously unified order. The installation offers an interactive relationship with the work and gallery space, encouraging viewers to approach the parts closely and to inspect them from every angle. Chan invites the visitor to experience these different perspectives as they wander among the sculptural elements, transforming their static completeness into an expansive ‘universe’ composed of many parts.

This can be appreciated as a series of conceptual and formal distinctions between the sculpture and the ground beneath it, as different arrangements of both figurative and abstract physical mass. Their experience is intended to feel their way into the sculptural space from within and become almost part of the sculpture at both its centre and periphery.

The following is the preview of TOTEM, a 10-minute video art by director Javier Ideami. Named after the exhibition, the video explores the theme of uncertainty that permeates the exhibition, in the context of the dialogue between materials, space and time.

The calm enigmatic face is the dominant motif in Wallace Chan's sculptures and it is one of the defining characteristics of the artist's imagination. Its ageless and androgynous facial features have a serene aura reminiscent of Buddhist imagery. While it resembles an ancient archetype, it possesses a timeless quality belonging to both past and future. — James Putnam

Rather, they symbolise the existence of a spirit, Gaia or Mother Nature. To me, it is not about creating symbols but rather a reflection of the spiritual practices of the self... The faces I created are probably influenced by religions, those of Gaia and Guanyin. The faces appeared during my spiritual practices, when I sought to reach the state of ‘non-self’. — Wallace Chan

Wallace Chan (b. 1956) is a Hong Kong-based, self-trained artist whose practice encompasses jewellery, sculpture and carving. He has been carving gemstones since the age of 16, drawing his inspiration from nature and Chinese motifs. He developed his skills and learnt the art of Western sculpture by visiting Christian cemeteries and admiring the marble sculptures of saints and angels. After six months of devoted monkhood in the early 2000s and, having given up all his possessions, Chan found himself in the complete absence of artistic resources. However, his passion for sculpture compelled him to create works using affordable materials like concrete, copper and stainless steel. After many years of careful research and experimentation, Chan developed a method of working with titanium, initially for his jewellery and more recently for his large-scale sculptures.

Chan has had solo exhibitions at Canary Wharf (London, 2022); Fondaco Marcello (Venice, 2021); Asia House (London, 2019); Christie’s (Hong Kong, 2019; Shanghai, 2021); the Gemological Institute of America Museum (Carlsbad, 2011); the Capital Museum (Beijing, 2010); Kaohsiung Museum of History (Taiwan, 1999); and Deutsches Edelsteinmuseum (Idar-Oberstein, 1992).

He has given talks and lectures at Tongji University (Shanghai, 2021); DIVA Museum (Antwerp, 2021); De Maastricht Academy of Fine Arts and Design (Maastricht, 2020); the British Museum (London, 2019); Royal College of Art (London, 2019); University of Hong Kong (Hong Kong, 2019); Christie’s Education (Hong Kong, 2019); Sarabande Foundation: Established by Lee Alexander McQueen (London, 2018); Sciences Po (Paris, 2018); Harvard University (Cambridge, 2017); Central Saint Martins (London, 2017); V&A Museum (London, 2016).

His works are in the permanent collections of the British Museum (2019), the Beijing Capital Museum (2010) and the Ningbo Museum (2010).

With special thanks to Yassmin Ghandehari, Francois Curiel, Yang Liu, Caterina Ying and Luigi Hu.

Our heartfelt thanks also go to Digby Halsby, Elizabeth Flanagan, Julia Safe, Kerr McIlwraith and Tilly Grant of Flint Culture; Bianca Arrivabene, Mascia Pavon, Sue Ellen Pavin and Lucille Datta of A CONSULTING; architect Alessandro Borgomainerio of AB VENICE; engineer Nicola Ferrari of ST Servizi Tecnici; designer and publisher Tim Barnes of the wind in the trees; composer Alistair Smith; and art historian Cristina Beltrami.

Other stories

In 2021, Chan’s first-ever large-scale sculpture and installation art exhibition, TITANS: A dialogue between materials, space and time, curated by James Putnam, former curator at the British Museum, was held at Fondaco Marcello, Venice in Italy.

In 2022, TITANS: A dialogue between materials, space and time is exhibited at Canary Wharf in London as part of the district's ongoing public sculpture programme.